Easter Wings

by George Herbert, (1593 – 1633)

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore:

With thee

O let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me.My tender age in sorrow did beginne:

And still with sicknesses and shame

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne.

With thee

Let me combine,

And feel this day thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine,

Affliction shall advance the flight in me.

I have a bit of print-nerdery to discuss today, so I’ll get right to it:

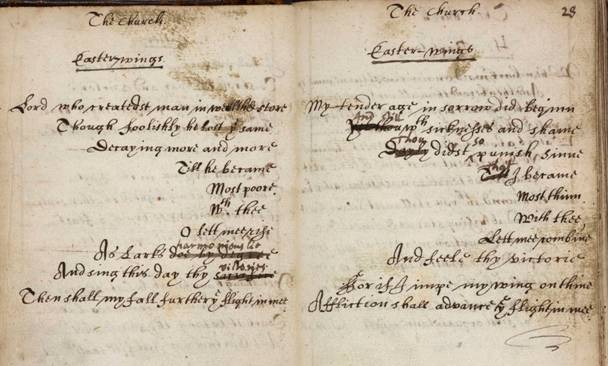

The 17th century Welsh poet, George Herbert, was a parish priest and a thoughtful religious poet (pretty much all poetry was either religious or utter bawdy doggerel back then – all extremes). His lovely chancery-style writing with pen and ink in his own poetry journal makes me a little envious (Oh, that I could write like that), and you can clearly see the way he intended the printer to lay out the type – to give the appearance of wings, an imagery repeated in the poem itself.

This pair of poems deals in both flight and falling – with paradox. The phrases “then shall the fall further the flight in me” and “affliction shall advance the flight in me” clearly underscore the paradox. If you’re saying, “Huh?” the fall referred to as the ultimate line in the first wing is the Judeo-Christian idea of the Fall of humanity into sin in the Garden of Eden — there was and possibly is a religious theory that Adam and Eve’s screwup was A Good Thing, so that Divinity could show off to the universe Its Holy Awesome. Take that as you will.

The final line of the second poem relies on the line above it – imping a wing is a falconer’s term. To imp a feather is to graft it – to take a broken feather and attach a healthy one to a needy bird. This is perhaps best understood like a hair implant; the feather no longer exactly alive, but taking root where needed. So, if he’s imping his wing onto that holy “thine,” he’s… taking his broken wing and putting it on the whole wing, and somehow expecting that affliction to advance his flight?

If that doesn’t make sense to you, that’s okay. Paradox doesn’t always make sense, and this paradox is a theological one, in that many people believe that our connection, our grafting, to Divinity doesn’t happen to us, but that we are grafted, useless and unfixable, into a larger, stronger pair of wings, to …find flight again.

Maybe there’s no flight, without falling…

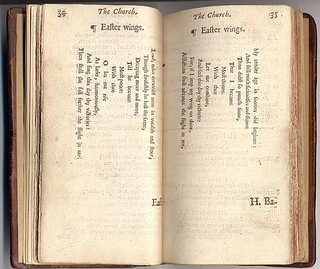

This poem was first published in 1633, the year of Herbert’s death, and is a cherished and popular Welsh poem. The typeset version pictured is from the original — when the poem was first published in 1633, and it was printed on two pages of a book, sideways, so that the lines suggest two birds flying upwards, with their wings spread out.

Herbert is using a form of poetry called carmen figuration, which was having a resurgence in the 17th century, and had previously been popular with the ancient Greeks. Which is also all kinds of cool. At least I think so. 😉