Tandy is still wearing her suit after church, picking nervously at the hem of her Harris tweed skirt. She has put on some weight, but her eyes are still huge in her too thin face, and her crossed arms are all angles and elbows as she stands and stares out of the window.

She looks so much better now that it is hard to see her as the same woman who arrived here two months ago, looking hag-ridden and death-shadowed, her hair thin atop her head where he had yanked it, trying to get at her face one last time. I have only seen him once, and it was dark that night, and he would not come inside my grandmother’s house. I always wonder if his face is battered and scarred. I always wonder if she gives as ‘good’ as she gets.

At least she’s calmed down a bit. Tandy was so manic when she arrived that my flesh would crawl every time she looked at me. Her voice reminded me of the rattle of dice, her conversation a gamble flung across an anonymous table, her direction uncertain, her destination unknowable. At least she’s calmed down some. For all the good it will do her now.

On the shallow church steps, the minister had taken Tandy’s hand and paused, solemnly looking into her upturned face, his eyes somber. He hadn’t seemed to mind that he was holding up the rest of the line of worshipers, anxious to get out to their cars and into their homes, out of their stuffy suits and into their sweats and slippers and pot roasts.

“Estandia, I understand you’re going home.” His rumbling voice had not formed a question.

“Tomorrow. Very early.” Tandy, with a wincing smile, leaned away from the large man.

The minister’s voice was as gentle as he could make it. “Take… care of yourself, won’t you?”

Tandy smiled meaninglessly, her eyes seemingly disconnected from the content of her head.

“Take care yourself, pastor,” she replied jauntily, slipping into the crowd of the faithful, their Sabbath best as concealing as fall foliage…

Mama has called us to the table for dinner, but Tandy is still standing in the den, futzing with the buttons on her jacket vacantly. She shifts on her thin legs, her feet encased in the leather pumps Mama loaned her. Tandy left her dress shoes when she left home, packing only odd bits of ephemera, the flotsam and jetsam of what had been within reach in the tumbled rooms of her house. I overheard my mother tell my father that the house was almost destroyed – furniture broken, pottery shattered, clothes strewn. “That house is a war zone,” she said.

Tandy is going back to that house. Tomorrow.

After the service, Brenda and Darelle caught up with Tandy at the car.

“Don’t make us come down to Texas, now,” Brenda warned in her usual mix of humor and threat. “Don’t make me come down there and kick your butt. You take care.”

Darelle closed her eyes and sighed. “She doesn’t need anybody else kicking her butt,” she murmured sotto voce, and Brenda had the grace to look chagrined.

“Take care of yourself, girl,” she reiterated nervously in a high, bright voice. “Just let us know how you’re doing.”

Darelle looked at Tandy gravely, biting her top lip. “Tandy,” she began hesitantly…

“Goodbye, my dear,” Tandy caroled, moving in close, bussing Darelle cheerfully on her round cheek. “You girls stay sweet. ‘Bye now. Take care. Take care…”

“Tandy.” Mama is gently drawing her sister toward the table. “It won’t stay hot all day.” Tandy stumbles a bit, lost in her reverie, but then her smile brightens, and she practically lunges toward the table, pulling Mama along in her wake.

“Everything looks great, Deenie,” Tandy grins, invoking my mother’s baby name while surveying the loaded table, reaching out for a piece of bread, then pulling her hand back at my father’s glance. “I could eat a horse,” she continues, then brays raucously at her little joke. Cringing, I grope for Mac’s hand under the table.

Aunt Tandy is leaving tomorrow, very early, to board a plane and return to her big house in Texas. Aunt Tandy’s husband has been phoning and phoning, initiating friendly banal conversation.

How’re ya’ll doin’ up there? Is it raining yet? Ya’ll been up to Frisco?

Apparently, now that the hairline fracture of Tandy’s skull is healed, all is forgiven. Now that the bruises have yellowed and faded, it is all right for him to make mention of her return. The locked room where the paramedics resuscitated her body, the hospital room where she lay with restraints upon her spindly arms lest she do herself some further harm are all a part of ancient history. Bewildered, we stand around wordlessly as Tandy packs, unwilling participants in her roulette game. I look at my poor family, locked in our own private combat. We don’t know how to act in someone else’s war. And Mac, so new to our epic struggle, is still trying to understand what he has gotten himself into…

By the time my father brings in the dessert, I long to stopper my ears and cease this rattling flow of conversation. My aunt is in rare form, laughing and joking and spinning off into little stories of her time in Hawaii, and how she was tempted to really give someone the “one fry” they asked for when she worked at a fast food joint on the Big Island. Now she is off and away on another topic entirely, debating with my father the origins of German Chocolate Cake, when coconut isn’t from Germany, and neither is chocolate. “They’re both New World foods,” she insists earnestly. “This should be called something else entirely.”

My memories of Tandy’s time in Hawaii culminated with her coming to “stay for awhile” with my cousin Melita, then three. Tandy’s arms and legs had been marked with funny yellow splotches. At six, I had thought that she’d had chicken pox. She told funny stories, though. It didn’t matter that she had old scars.

“It’s based on Black Forest torte,” my father is waxing expansive, the resident expert on Germany now. I roll my eyes and ignore them both.

Tandy’s relationship with my father is based solely on bantering insults and mock aggression. Mostly, my father’s wrathful temperament makes his aggression real, but we’re being polite these days, all of us stepping lightly, treating Tandy like she will shatter if we speak too loudly. After twenty five years of her particular brand of hell, I’m not sure if anti-aircraft missiles would make a difference, but we all try… we are all trying… it is all very trying…

I am shredding the bread with the icy lump of margarine which my father neglected to take out of the fridge until the last minute, as usual. I am thinking that it is his little conspiracy, we should eat our bread plain and like it, darn it, when suddenly my brains snaps back into my head, and I tune in to Tandy’s voice. My father has just told her she doesn’t need a slice of cake that big, and Tandy’s expression has taken on a flirtatious petulance, obscene somehow on her death’s head face, and she is crossing her stick thin arms across her narrow chest.

“Stop telling me what to do,” Tandy pouts. She turns to us, laughing, “Your father doesn’t think I’m forty-six, he treats me like I’m six! You’d tell me every breath to take,” she complains to my father.

Around the table, we all chuckle politely, my mother smiling courteously, all of us playing into the genteel family scene.

“He’s just getting you ready to go home, isn’t he?” Mac interjects blandly, taking a bite of salad.

* * * *

There is a silent heartbeat, and then my father guffaws. My mother breaks into a nervous smile, more a grimace, and shakes her head. My older sister snorts and busies herself with pouring the juice. Tandy is fully present, for once, eyes wide and is that… anger on her face?

My rapidly indrawn breath comes out in a hiss between my teeth, and I cast an exasperated glance at Himself. His left eyebrow jumps, a nervous tic, and I immediately give him a quick nudge, reassurance. I know how much it takes to speak the truth at my father’s dinner table.

“I had nothing to do with that,” I betray him cheerfully, reanimating us. “I’m just sitting next to him.”

“You! You!” Tandy sputters, pointing her fork at Himself. The brief glimpse beneath her veneer is over, and her smile is back. But the mask is tarnished, there is a sadness to her voice, and her chin is tense.

“You are so bad,” my sister exclaims.

The conversation stutters to life again on different topics. We go back to talking about the cake. Yes, the cake. That seems safe…

Early, early this morning, Tandy got on a plane to go back to her big house in Texas. Her husband of twenty-eight years was waiting for her. There was a reunion.

My mother offered to pay Tandy’s way out for Thanksgiving, but she won’t come. She has her grandchildren to consider, her four children who ignore her and “borrow” her car and her cash card. Her husband, who leaves holes in the drywall with his fists. Tandy has to call the workmen to repair the bedroom doors. Those lovely French doors that the paramedics damaged so badly…

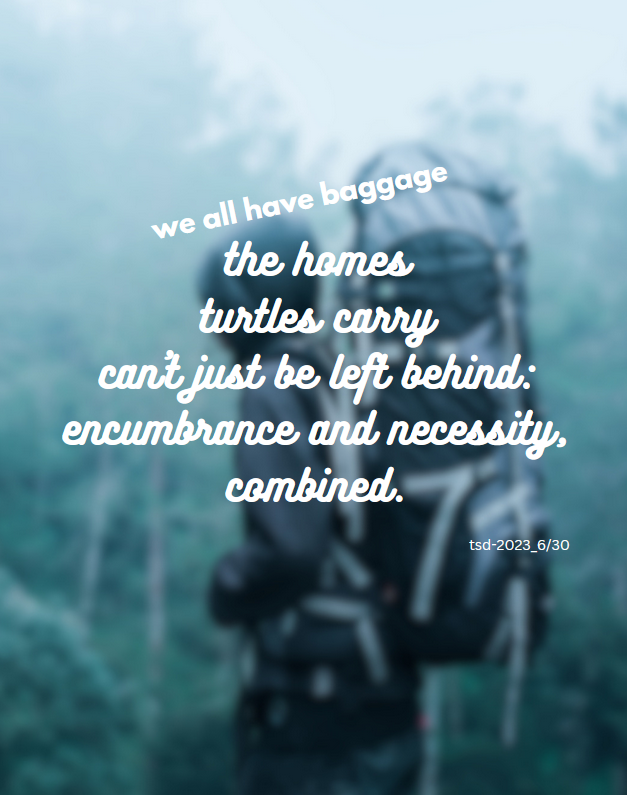

I wonder when I will see her again. Sometimes, I don’t think I will. She always goes back. Mac says it’s like she’s the iron to his magnet.

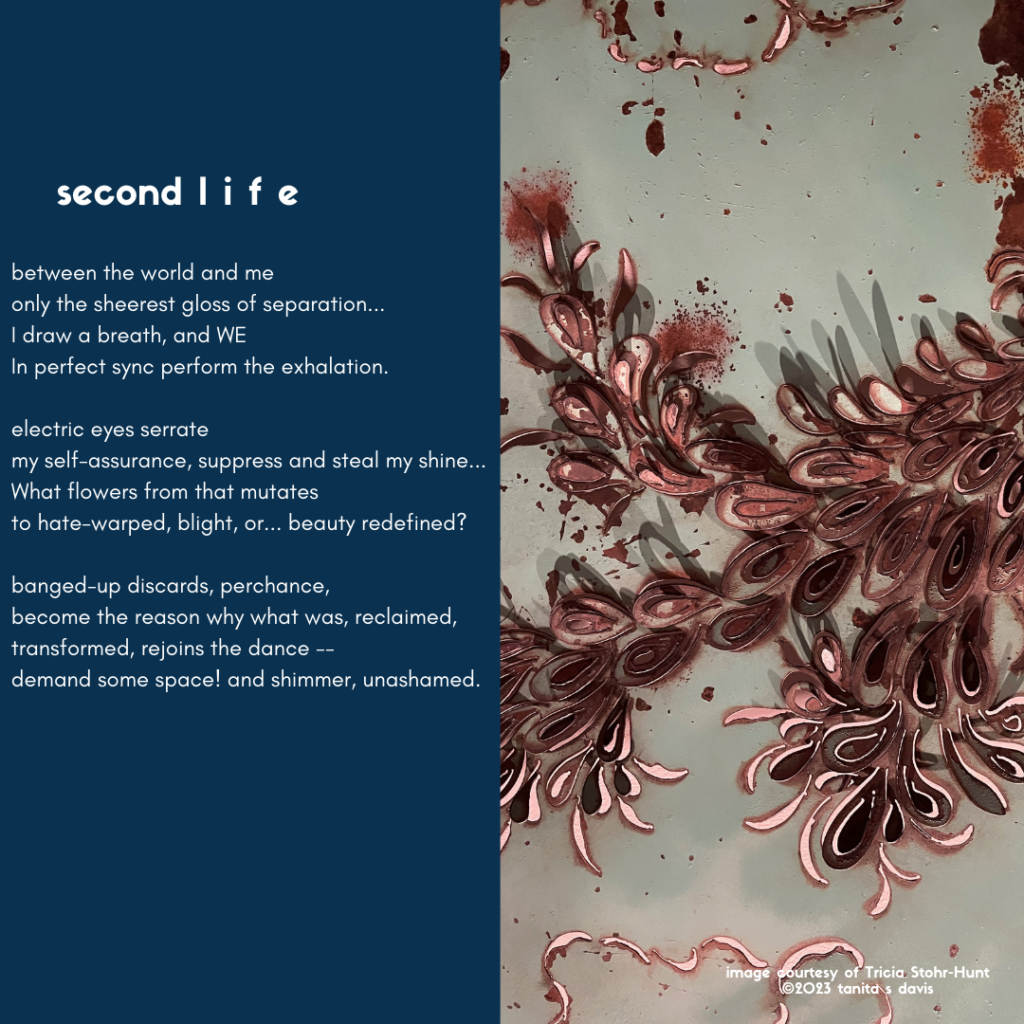

I think it’s more like she’s the sailor to the rocks, the lemming to his cliff, the bite of the razor to her sickened flesh. She is drunk on this illness, led toward him by some unknowable call.

She will go back, and she will fry. She’s like a moth to a flame. Be ware, ladies. He’s irresistible.