This is a 2017 post from my family blog. It seemed a fitting repost.

It was the Mozart solo she’d had her heart set on. A simple kyrie, appropriate for ten-year-olds, but the rising descant over the chorus made her feel unnameable things, and she wanted to sing it with all her heart.

In parochial schools in those days, there wasn’t much else to do but participate in the arts. There was no prom king or queen, no dances, no competitive sports. Instead, the boys took piano, and the girls played the flute – or, at least it seemed like everyone in her grade did. Twenty-some girls on flutes, and not a one of them with the courage to do something original, like learn the French horn. But, it was what it was – middle school in the 80’s.

The Kyrie was the first real classical music they’d ever done, so out of the mundane realm of kids’ songs they’d done before. Everyone was aware that they were in the presence of Grown-up Music, and acted accordingly. Desire to show themselves as grown up – and sing that descant – was intense. Her choir teacher knew she wanted that solo, knew she was a soprano who could consistently hit the right notes, but, weighing his choice by scales she could not read said, “Well, sweetie, we’ll give this solo to Sheley. We’ll save a nice, juicy Spiritual for you.”

But, she didn’t want the Spiritual. She wanted the Mozart.

In college, she was to remember this moment when visiting home on a weekend to sing with an ensemble. The rehearsal was early – the music was lackluster, and the director was getting desperate as the singers’ yawns increased.

“Sing it more black,” the director urged her, finally finding both scapegoat and fix.

She stopped singing altogether, bewildered. “What? What does that even mean?”

“Well… you know,” the director gestured vaguely. “More black.”

She vanished behind a brittle smile. “You mean, with more of a swing? With more of a backbeat? With more syncopation? What?”

She kept her voice even, because she had learned it did no good to scream.

Fast forward to a progressive party in San Francisco, where, armed with cameras, teams of teens and twentysomethings were on a scavenger hunt. One of the requirements was for participants to take a picture of themselves on or near a stage. Half the group pressed to simply go to Max’s Opera Cafe and take a group shot with a singing waiter. Another vocal male found a jazz bar on one of the piers, and insisted she go inside, take the mic, and ‘scat.’

“Scat?” she echoed, for a moment setting aside the breath-stealing idiocy and horror of making an unsolicited performance in a private club.

“Yeah, scat,” he said, “Like Ella Fitzgerald. You know…scat!”

This time, embarrassment came mingled with humiliation, as the entire group began to wheedle. “No, you guys. Really…no.”

Fast forward even further, to singing with a quartet, in which the music director and the pastor – both white males – donned sunglasses and capered to the spiritual style hymn in the style of the Blues Brothers. Fleeing during a break, she called her sisters, asking them what to do, how to act. They stood and listened while she laughed, tears streaming, down a face so hot they evaporated. “But, why am I embarrassed?” she kept asking. “They’re behaving like jackasses, and I’m embarrassed? I feel like they’re making fun of me, and it’s humiliating, but why am I the one who is feeling …stupid?

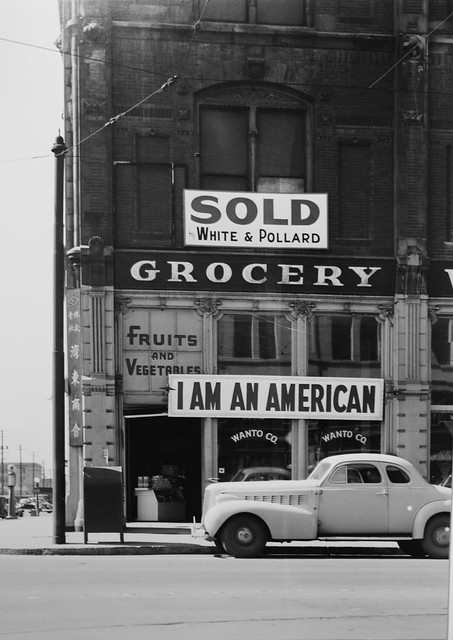

The shame didn’t make sense, but by then she had learned that few things did, when microaggressions – casual racism – was added to the mix. Musically, it meant that people assumed she wanted – always – to sing gospel music, even though she did other music well. It meant that people assumed she could break into Janet Jackson improvised choreography, that she could imitate the vocal rhythms of Bobby McFerrin on a whim. It meant that instead of who was in front of them, someone whose eclectic tastes ran from the weird to the classical with many stops in between, all they saw was myriad aspects of what – The Other combined into a single person, on whom they could glue myriad of labels, none of which were hers.

It was exhausting.

We fast forward one last time, but our time machine is about out of steam. Now see it has limped to a stop at chamber rehearsal, where a gleeful last-minute addition means another entry into the program, another song to be learned. “Oh, it’ll be quick,” the director encourages the panicky singers. “It’s just two parts, in Swahili. Uh, just read the pronunciation as is — I’m sure it’ll be fine.”

“It’ll be fine.” A startling phrase, after the lengthy lectures about pronouncing German as to not “sound like hillbillies.” Unexpected, after the long-winded arguments about “church Latin” vs. classical Latin pronunciations. Jarring, after the many long lectures about pronunciation of Hebrew consonants vs. Yiddish, of Argentinian Spanish vs. Mexican. Shocking, that an entire language is mischaracterized (the people are Swahili; the language, Kiswahili) and shrugged off as “nothing to worry about.” As the translation was cooed over, in ways the translations of European languages were not (“Ooh, how sweet!”), she found herself… conflicted.

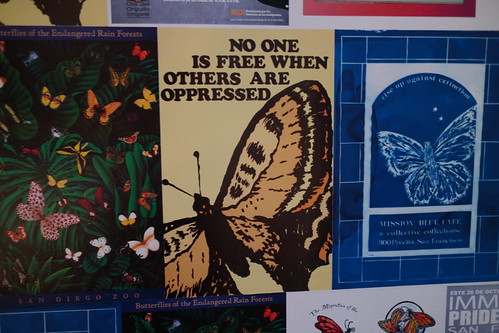

The composer’s name was American, and a thorough search uncovered no African translator. Deeper research revealed that the composer’s translation didn’t match a word-for-word translation of Kiswahili words, that the tune was from a Nigerian harvest song. There was no citation as to where the words came from, no African educator or musician listed. She feared that they were singing an imaginary lullaby, with imaginary text, the rocking 6/4 tempo convenient but false. This was music selected by an intentional community made up of good people, people whose stated goals were to bring parity, inclusiveness, and justice to the world – yet they easily diminuitized the importance of a tribal people and its language as “cute,” but ultimately too insignificant to merit concern or further study.

Perhaps, as was implied, it wasn’t that important, in a world where wrongs of greater significance loomed large. Perhaps it was merely good enough for an American winter festival – not exactly religious, Christmas, not exactly non-religious, Solstice. Not exactly meaningless… and not exactly meaningful.

Or, perhaps it was as infuriating and confusing as everything else she had ever encountered.

Edited to Add: PS – you will be gratified to know that speaking up helped a little. The director phoned a friend in Kenya, determined that the text is “maybe Nigerian” and not at all Kiswahili, and promised to do due diligence to find out what he could, and add his findings – or lack of such – to the program notes. Intentional communities such as choirs and churches – and libraries, schools, and other places – must be intersectional in their inclusivity, thinking through the many ways we as people can belong to various communities, and doing our best to come to each of them with thoughtfulness, respect and appreciation, thinking not just of our individual needs, but how to serve a whole, which is the sum of its parts. As has become so readily apparent, it is tricky, but if we draw each other back to the road when we wander off, it can be done. It must be.