You have gone downtown to do some shopping.

You are walking backwards, because sometimes you like to,

and you bump into a crocodile.What do you say, dear?

It’s a conundrum, isn’t it?

Nope, you’re not in the wrong place, and yes, I’m very early for the first-Monday-of-the-month Wicked Cool challenge (in which I admit to spotty participation). I don’t normally do picture books, yet today is the birthday of Sesyle Joslin, and since she and I practically share a name (always wondered what that S. was for, didn’t you? Swap around a few letters and add an ‘a’ and we’re right on)I wanted to raise my mug of hot and frothy Mexican chocolate to the quirky, funny, whimsical writer and her stupendous nineteen picture books.

You have gone to a tropical island with your friend, the Pirate, to help him find buried treasure. You spend the entire morning digging for it, but then — just as you uncover a large treasure chest — the Pirate’s cook rings a bell. “Luncheon is now being served,” he says.

What do you do, dear?

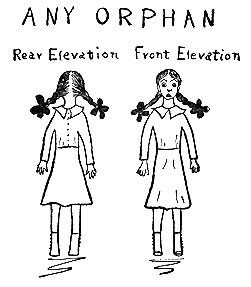

What Do You Say, Dear? published in 1958, and What Do You Do, Dear?, 1961, are two of the best known of Sesyle’s books (thanks to illustrator Maurice Sendak), wherein children of gentle breeding are put in

situations of utmost and increasingly ridiculous peril. Quick thinking is the only thing to help you when polar bears and bandits abound. But what about your manners? When the lady you’re forcing to walk the plank drops her handkerchief? What do you do, dear? When the lad who was bitten by a dinosaur thanks you for saving his life after you’ve given him a Band-Aid? What do you say, dear?

You are a cowboy riding around the range.

Suddenly Bad Nose Bill comes up behind

you with a gun. He says, “Would you like

me to shoot a hole in your head?”What do you say, dear?

Honestly, the airily tossed back, “No, thank you,” on the next page as the kid rides away cracks me up every time. That Bad Nose Bill dude just never learns. Granted, these days the gun-to-the-head scenario Sendak sketches would NOT play out well in picture book land AT ALL, but it was all in good fun back then, when Cowboys & Indians was just an imaginary “harmless” war game. (Hm.)

I think Sesyle’s dual language books are also fascinating and priceless. Spaghetti for Breakfast, and Other Useful Phrases In Italian and English gives the intrepid traveler something to say on vacation — to avoid pasta first thing in the morning. Or, not, as the case may be. Or, how about There is a Bull on my Balcony, “Hay un toro en mi balcón,” and Other Useful Phrases in Spanish and English for Young Ladies and Gentlemen Going Abroad or Staying at Home? Doesn’t that sound delightful? I love that it’s for both gentleman and ladies, for those armchair travelers and those actually boarding planes. The very droll length and wordiness of the titles are guaranteed to give adults a hoot, while providing fun and informative tips for kids.

Need to know just how to begin that letter to your hoary old great-uncle? Dear Dragon… and Other Useful Letter Forms for Young Ladies and Gentlemen Engaged in Everyday Correspondence can help you out. Every eventuality is covered, in Sesyle’s world. Dragon in your bed? You can tell it to excuse itself in English OR in French. Treasure-hunting before lunch? You and your friend, Pirate, will please wash your hands before you get to the table. Are you a Native person smoking a peace pipe with visiting Cowboys, and you swallow a bit of smoke? Even then, there’s a right thing to say. (And it has nothing to do with how non-PC that whole peace-pipe scenario might be.) There’s a proper procedure for every occasion, and Ms. Joslin has every occurrence covered.

Sesyle Joslin wrote other picture books that I have yet to run down, which feature baby elephants, peanut sharing, a stolen alphabet, lady spies and muffin men, smugglers, owls, and more. Her piquant sense of the ridiculous makes these classics something I’m eager to find.

I was a bit disappointed that there isn’t more information available on Ms. Joslin, who won a Caldecott Honor, and was a two-time Horn Book Fanfare Best Book recipient. How could a public who loved her just let her disappear like that? Well, I forgive her, if she was an introvert; I know how that goes. My information has her being born in 1929, so she could be alive somewhere, a well-preserved and etiquette-correct dame in her eighties, still knowing exactly what to say at all times. What little information I found on her informs me that in 1950, she married novelist Al Hine (1915-1974), and together they embarked on a series of historical fiction children’s books together, under the pseudonym of G.B. Kirtland, and a picture book, Is There A Mouse in the House? under the pseudonym Josephine Gibson.

[Details from Children’s Books & Their Creators: An invitation to the feast of twentieth century children’s literature, edited by Anita Silvey, Houghton Mifflin, © 1995 p.358]

We still love you, and your books are still funny, after all these years: Happy Birthday, dear Sesyle.

Despite the Consumer Product Safety people thinking it should be banned — all that nasty unsafe pre-1985 ink and all — you can still buy many of Sesyle Joslin’s books, including What Do You Say, Dear? and What Do You Do, Dear? from Alibris or other independent bookstores near you!

X-posted at Wonderland.

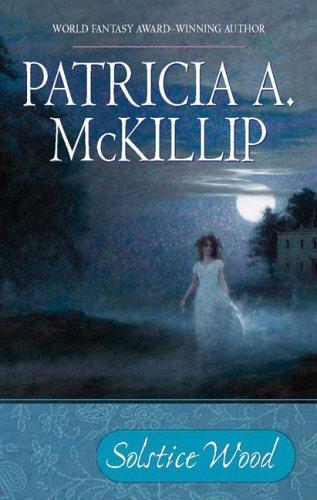

It’s a modern faerytale from the queen of mythical and medieval.

It’s a modern faerytale from the queen of mythical and medieval.